BC Premier David Eby made a dangerous and misleading statement last week when he described a long-acting opioid agonist therapy to be “almost like a vaccine against overdose.”

Extended-release buprenorphine – commonly referred to as its brand name Sublocade – is in no way similar to a vaccine. This misrepresentation does a disservice to public perceptions of both opioid agonist treatments (OAT) and vaccines, during a rising tide of vaccine hesitancy and a toxic drug public health emergency. It also fails to adequately demonstrate the uneven and unknown risks of using Sublocade across different patient populations.

Eby made the loose analogy at a press conference alongside government advisor Daniel Vigo, where the duo announced Vigo’s new guidelines for detaining youth under the Mental Health Act for reasons related to substance use disorder alone. The guidelines interpret how to use the MHA to carry out involuntary substance use treatment against youth. The guidelines include forcing youth into a state of withdrawal before injecting them with Sublocade without their consent.

This was not the only sensationalized or misleading language used by Eby and Vigo during an announcement that – once again – revealed persistent government failure to provide youth with adequate safety during a nearly decade-long public health emergency.

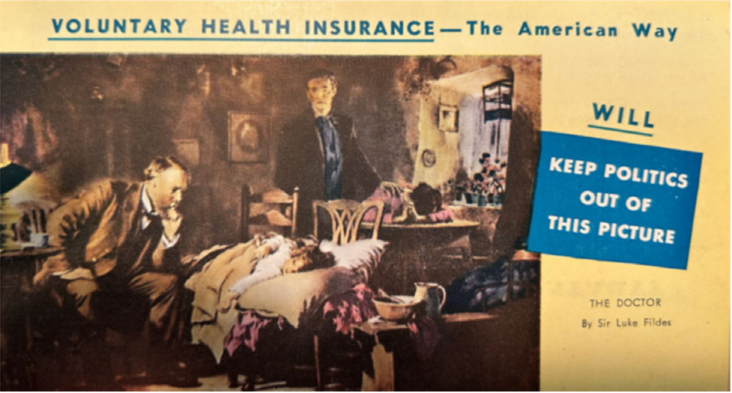

Vigo invoked The Doctor, a painting by Luke Fildes, famously used by the American Medical Association as part of their campaign against national healthcare in the 1940s. Vigo positioned the painting as an analogy for how he sees himself in the role of a physician when working with youth. Meanwhile, Eby boiled down his endorsement of Vigo’s guidelines to being the only alternative to “letting somebody die in the gutter.”

Flyer from the American Medical Association's campaign against a public healthcare system. 1949. California State Archives.

Vigo’s forced treatment guidelines may sound oddly familiar given the BC NDP’s 2020 attempt to pass amendments to the Mental Health Act with Bill 22. Bill 22, colloquially called the “Youth Overdose Bill,” sought to expand the use of the MHA to detain youth with diagnosed substance use disorder following an overdose for up to seven days.

The Youth Overdose Bill was shut down after opposition from Indigenous, community/youth, legal and healthcare worker groups. The province’s Representative for Children and Youth, Human Rights Commissioner, and Chief Coroner all came out publicly against the bill.

In a joint letter at the time, Pivot Legal and the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition wrote, “compulsory detention and treatment in the context of substance use give rise to a range of potential drug-related harms and human rights abuses, including deterred access to harm reduction services out of fear of apprehension.”

Unlike the Youth Overdose Bill, Vigo’s new guidelines are not legislation. As one Vancouver doctor posted to Bluesky, “this is just a piece of paper with [a] Government logo on it…it's not a peer-reviewed paper or clinical guideline; it's one random dude’s thoughts and it's frankly insulting to assume that clinicians should accept it at all.”

Roughly 300 healthcare workers, including more than 50 physician and nurse practitioners, have signed a refusal campaign against implementing Vigo’s substance use disorder-based interpretations of the MHA.

But Vigo’s interpretations of the MHA are being backed by the province – and should be taken seriously for their potential to cause harm.

Add your name to join the refusal campaign!

Realities of buprenorphine

Sublocade – an extended-release formula of buprenorphine patented by the pharmaceutical company Indivior – is a long-acting opioid agonist therapy with low rates of continual use over time, as well as limited voluntary uptake.

Indeed, the Vancouver-based Indivior-funded study conducted to assess Suboclade’s effectiveness was not able to recruit its desired sample size, even after researchers eased the criteria for participation among adults. Among the adult participants who did enroll, only 32 per cent completed the full six-month study, while 68 per cent of participants abandoned it.

Broader measures of Sublocade retention rates among adults across the US have shown that they fall to 13.5 per cent at the six month mark. Retention is only a metric of ongoing use, not patient well-being. Retention does not reflect satisfaction, a reduced sense of dehumanization, nor improved quality of life outcomes.

In addition to these limits, research can hardly keep up with the pace of changes to the drug supply in regions like British Columbia, where components of the unregulated drug supply shift rapidly (as is projected to continue under prohibitionist-style drug laws).

Before starting with Sublocade, a person must be in acute opioid withdrawal – at the highest intensity that they can muster. According to clinical guidelines, this means someone must go through at least twelve hours of abstinence from using short-acting opioids or 48 hours for long-acting opioids.

Due to the incredibly difficult nature of being in a state of withdrawal when reliant on prescription opioids or the increasingly complex unregulated supply, the process of starting Sublocade can be excruciatingly painful, often described as torturous.

This reality and people’s diverse thresholds for pain puts people at an unpredictable risk of experiencing severe precipitated withdrawal – a form of withdrawal generated by taking buprenorphine, which the suggested period of abstinence is meant to reduce or bypass.

As one author of this article, Heather Tunold, shares from her experience:

“For three days of precipitated withdrawal, I reached a level of suffering I can only describe as torture. I have never wished for death, but in that window I imagined it as a reprieve. And that was with community, support, and love around me—conditions many young people will not have if this is forced on them. I could barely withstand the excruciating panic that precipitated withdrawal put me in…constant high blood pressure, it felt like my organs were shutting down, every nerve ending lit up like fire. My nervous system on overdrive. My legs and arms thrashed with involuntary restlessness I could not control, my body swung between hot flashes, violent cold sweats and freezing shocks, and the dissociation pulled me so far from myself I wasn’t sure I’d come back.”

Health Canada’s product monograph – the standard federal guidance document on safety and effectiveness of approved medications – says that “[n]o data are available to Health Canada in patients 18 or under.” Sublocade is not endorsed by Health Canada as a first-line prescription for youth in any specific circumstance.

Sublocade also cannot address some of the primary components of the current street supply, including benzodiazepines. Unmanaged benzodiazepine withdrawal comes with its own difficulties and pain particularly for people with further mental health diagnoses. Abrupt cessation of benzodiazepines can cause death.

Once Sublocade is injected it cannot simply be undone, as the medication can stay in a person’s system over an extended period of time.

Many young people who use drugs have described forced, highly medicalized treatment as alienating and coercive, emphasizing that these services prioritized oversight and pharmacological control while replicating institutional harms they’ve experienced throughout their lives, and neglecting the relational trust that real care requires. It is no wonder that youth have continuously raised concerns about how experiences and/or threats of involuntary treatment can drive them away from health and social services, including cautiousness about seeking emergency responders when their health or lives are at risk.

Sublocade is not a vaccine or anti-overdose drug

Some research has linked prescriptions of OAT, particularly buprenorphine, to reduced chances of overdose after discharge from treatment. This includes one study exploring 2016–2017 data from Connecticut and a larger US-wide study that used data from 2015–2017. These types of associations have led to expansive use of Sublocade at residential detox facilities and in hospitals in at least some regions in BC. But these types of research findings do not tell a full story.

First, to be clear, there are no shared mechanisms or characteristics between Sublocade and vaccines. Unlike vaccines, Sublocade and other OAT do not confer immunity or protection through a shared biological mechanism. Vaccines prime the immune system to recognize and fight specific pathogens, often providing long-term or lifetime protection. OAT, by contrast, may stabilize opioid tolerance and reduce cravings for a short period, but overdose risk remains shaped by far more volatile and structural factors: a toxic, unregulated drug supply, interrupted tolerance following incarceration, and the trauma of forced or coercive treatment.

Second, the hazardousness of Eby and Vigo’s misrepresentations should not be understated. The bioavailability of Sublocade has a number of peaks and troughs throughout its extended release cycle, which are experienced quite diversely. Eby’s comment that Sublocade “lasts for 30 days” as a protective factor against overdose is unfounded and could be dangerously misleading for youth and their support networks. Initial Sublocade doses are released over a 28 – 42 day period, but this does not occur at a consistent strength, and research has not shown that it is a protective factor against opioid overdose during its full release period.

Off-label use of prescription medication, however, is a common and important tool in addressing health concerns. But this type of treatment should require that patients engage in a consensual management plan having in-depth conversations with prescribers to ensure intimate understanding of the benefits and potential risks associated with its use.

This level of engagement appears absent in the suggested pathway that Vigo and the BC NDP are promoting. Given what we know of the limited use and retention of Sublocade in voluntary patients and the broad understanding and reflected research that coercive treatment has even greater risk for harm and overdose, Vigo’s guidelines are perplexing.

It is important that youth continue to be provided with appropriate options for accessing short-acting and long-acting OAT medications on a voluntary basis, in situations where they are fully informed. Sublocade can and will be an effective treatment for a significant number of people who use drugs.

Carceral treatment of youth

Youth are systemically abandoned when it comes to the horrors of the toxic drug supply emergency. This abandonment includes being left out of the already tragically inadequate number of interventions that have been permitted to reduce the death toll.

There are no youth-friendly supervised use sites in BC; the decriminalization model did not apply to youth (not before or after the ‘recriminalization’ amendment); there is no legal access for non-medicalized pharmaceutical alternatives for youth or adults; and access to sterile drug use equipment remains difficult and heavily stigmatized for youth. There are no formal supports or services specific to youth who have lost loved ones, including parents or guardians, to the public health emergency.

Within schools—institutions that should provide stability—the British Columbia School Trustees Association found that substance-use and overdose responses are “fragmented, inconsistent, and insufficient,” effectively leaving already-vulnerable youth to navigate a toxic drug crisis without meaningful support.

In 2022, the province withdrew funding and closed down the only voluntary youth detox facility in Vancouver, moving to home-based detox (presumably for youth who use drugs and have both homes and safe living environments). About 400 youth had stayed there in the year 2018, according to reporting by CBC News.

What has been expanded for youth during the toxic drug crisis are a limited number of beds at private recovery centres in a deregulated industry, where outcomes are not necessarily measured, and where former participants of these facilities have reported inhumane conditions and practices.

As of the 2023 Chief Coroner’s Death Review Panel report into the overdose public health emergency, the BC Coroners Service had not been empowered to track the deaths that occur at private treatment centers or directly after discharge. BC’s former Chief Coroner, Lisa Lapointe, also repeatedly recommended stronger oversight of private treatment centers, which have been given millions in funding under the guise of the toxic drug emergency.

BC NDP and Vigo continue with involuntary treatment expansion

Vigo opened the press conference by saying, “this is a very special day for BC children and families, and also for me, as a psychiatrist.” It came just a few days after the BC NDP increased liability protections for workers and police officers who employ the Mental Health Act, while providing no new protections for patients.

For his part, Vigo appears to have relied on five peer-reviewed studies to uphold the idea that Sublocade should be used for mental health reasons – these studies are from 1982 (x2), 1987, 1990 and 2014, respectively. All of this research is based on the short-acting form of buprenorphine.

Vigo appears to misrepresent the findings of a 2014 systematic review by partially quoting a sentence in its abstract. The abstract reads: “it is not only the anti-craving action of opiate agonism, but also its effectiveness on the psychopathological level that qualifies it as to be viewed as a powerful tool in treating mental illness.” Yet Vigo leaves out the first part of the sentence, which states, “the whole topic of opiate agonism merits is due for reconsideration.” The sentence is describing a theoretical suggestion, not a conclusion about the impacts of opioid agonists – and certainly not about Sublocade – as Vigo’s guidelines suggest.

Vigo’s guidelines then assert, “buprenorphine specifically proved effective against hallucinations and delusions,” by citing two sources: 1) one study that does not say that, and 2) a second study that explored the impacts of buprenorphine among 10 adults in 1982 for the first four hours after their dose, seven of whom noted a reduction in psychopathological symptoms. As the authors of the latter study accurately note, it is a significant preliminary finding, but it is certainly not proof of anything.

In all, Vigo’s work gives the feel of someone who just learned how to use an academic database or Google Scholar. And for all the pain this treatment could cause, youth who use drugs and their support networks deserve so much better than what Vigo’s BC NDP-endorsed guidelines suggest.