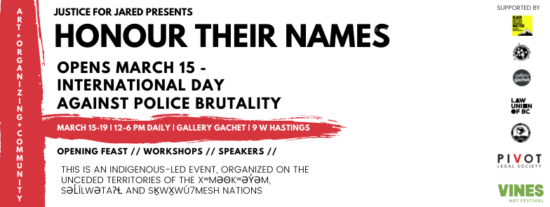

This year, an art exhibit and series of workshops have been organized to recognize International Day Against Police Brutality in so-called Vancouver, on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) Nations. The show, Honour Their Names, is organized by the Justice For Jared campaign, and is bringing attention to police murder and violence against Indigenous people across the territory colonially known as Canada. The exhibit will be held at Gallery Gachet, an artist-run centre in the Downtown Eastside that centres artists with experiences of mental health and social marginalization.

Honour Their Names features artwork designed to commemorate close to 90 Indigenous people who have been shot and killed by the police; this list includes leaders and land defenders, people in distress, people who were criminalized as youth and adults, and several families where multiple members were killed by police – such as Wasagamack First Nations members John Joseph Harper and his nephew Craig McDougall, who were both shot and killed by Winnipeg Police, and Algonquin brothers Johnny Junior Michel Dumont and Sandy Tarzan Michel, both killed by the Anishnabe Takonewini Police Service.

Honour Their Names was envisioned by Laura Holland, whose son Jared Lowndes was killed by the Campbell River RCMP on July 8, 2021. As an Indigenous woman and mother, an activist and organizer, this work is integral to Holland’s fight for justice – for her son, and for all the Jareds whose lives have been extinguished by colonial violence. Laura Linklater, a Métis woman connected to the ceremonial community in the Lower Mainland, is also a collaborator on the show. Linklater has designed pieces inspired by ribbon skirts and shirts, explaining:

We wear the ribbons as a symbol of resilience, sacredness, and survival. This tradition comes from the Plains tribes. These pieces are done to add beauty into our work of honouring relatives from across Turtle Island, with love and in memory of our lost ones.

The first International Day Against Police Brutality was organized in 1997, through the work of the Tiohtià:ke/Montreal-based collective Collectif Opposé à la Brutalité Policière (COBP) and members of the Black Flag in Switzerland. 2022 marks 25 years of international solidarity in organizing this day of resistance. Moroti George, Programming Coordinator at the gallery describes the inherent links between the criminalization of psychiatry and violent policing:

The criminalization of mental health and the policing of bodies that live with mental illnesses is incredibly harmful and works to oppress these bodies and further create a line of “difference” in western societies that revolves around the idea of the ‘normal.’

In most cases, in the west, the idea of the normal is inherently tied to ideals of whiteness and white societies, which further causes the criminalization of mental health to affect BIPOC people (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) insidiously and adversely.

The criminalization of mental illness and the policing of people who live with mental illnesses rarely consider how the trauma that Indigenous and Black people endure at the hands of the settler colonizer states manifest in the form of mental illness. In these cases, criminalization of mental illness does far more harm than good, as BIPOC people who live with mental illness do not need their bodies to be further policed and marginalized. Instead, the funds that support the states’ criminalization of mental illnesses could be redirected to organizations rooted in restorative justice and decolonization and interact with these people who live with mental illness through a lens of care and rootedness, as opposed to simply policing and marginalizing them.

Since the George Floyd uprisings of 2020 in the US, there has been sustained interest in anti-Black and anti-Indigenous policing and discrimination – legacies of colonialism and chattel slavery that shape both Canadian and American society. While Canadian police officers have been quick to say they are being criticized for American policing policy, they are erasing the realities of racist policing in Canada. Since 1989 there have been over 20 commissions and inquiries in Canada that relate to the criminalization of Indigenous people. This includes: the Marshall Inquiry (1989) that was precipitated by the wrongful conviction of Donald Marshall Jr., a Mi’kmaq man from Membertou, Nova Scotia; the Inquiry into the death of Neil Stonechild (2004), a Saulteaux teenager who was murdered by police during a Starlight Tour; and the Inquiry (2009) & Response (2011) to the Death of Frank Paul, a Mi’kmaq man from Elsipogtog, who died of forced exposure in Vancouver, found hours after he was dragged out of VPD custody into a nearby alley. As the Honour Their Names exhibit illustrates, Canadian police forces have stolen the lives of all too many people.

In a 2020 Mainlander article, VANDU Board Member Flora Munroe, a member of the Misipawistik Cree Nation, recounted the longstanding history of police violence and the corresponding lack of accountability:

The first cop ever investigated for any wrongdoing in Canada was way back in 1949. Back then the complaints went unheard and there were always ‘no grounds to investigate.’ Not that much has changed today. Still today the killing of so many natives is not properly reported and documented.

Disturbingly, since 2017, reviews of fatal police shootings reveal that an Indigenous person is 10 times more likely to be shot and killed by a cop than a white person. These statistics reflect how colonialism reverberates in every institution, including the criminalizing ‘justice’ systems that force Indigenous people into contact with police and incarceration. Despite more than 20 inquiries over more than 30 years, violence continues to be a routine feature of policing. Indigenous people are still killed in police and prison custody in BC and across Canada. In the total absence of complete restructuring or meaningful change, all we see are superficial, cosmetic changes: calls for increased training and education, modules on cultural sensitivity, and symbolic gestures that fall extremely short of change. And that’s the point. These are the ‘solutions’ we are stuck with as long as ‘Canada’ remains committed to its legacy of colonization, racism, and anti-poor logic.

BCCLA Policy Director Meghan McDermott highlights the enduring difficulties of holding police accountable through the mechanisms currently available:

As a lawyer engaged in police accountability, I am appalled by the brutal use of force that police use in our communities and the inadequate oversight systems that continue to clear them of any wrongdoing. Month after month we hear about new and devastating cases of death and trauma caused by police actions. Despite all the harm and suffering caused by police brutality, our governments are not willing to make the systemic change needed to uphold our human rights – our rights to be free from discrimination, to have liberty and security, to be free from torture, and our right to life itself.

Beyond inquiries and commissions, families have also been forced to put their trust into “independent oversight” bodies such as the Independent Investigations Office (IIO) in BC or the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) in Ontario. These bodies claim to be independent civilian agencies that have the power to both investigate and charge police officers with a criminal offence. Despite this mandate, agencies such as the IIO & SIU routinely fail to administer justice. Many investigators within these civilian organizations are former police officers themselves – in BC half of the IIO investigators are former police officers. In 2019 BC’s Attorney General, David Eby, actually reduced hiring limitations for the IIO. Previously, investigators who had been members of any BC police force within 5 years of their appointment could not be hired; AG Eby put forth an amendment reducing that restriction to 2 years. Former police officers from outside of BC can be hired immediately. The current systems of police accountability force families through legalistic bureaucracies that dehumanize them. Families find themselves struggling to make sense of confusing systems while they grapple with the unthinkable – a loved one dying at the hands of police, as investigated by yet more police.

In the wake of a police killing, families must contend with police officers, coroners, IIO investigators, media, social media commentators – all while picking up the pieces of their loved one’s death. Families have no access to support, independent from the IIO, nor funding for lawyers, advocates, or support workers to walk alongside them in this high-barrier process. While advocates have raised this issue with the provincial government, it’s clear BC has no interest in building systems for survivors, much less preventing police-caused deaths in the first place.

From my work, standing alongside family members and survivors of police violence, it is clear that attempts at reform are not working. In fact, reform is only buttressing these violent systems, and exhausting resources that could be redirected toward more effective services if we actually defunded police. When we push back on police involvement in ‘wellness checks,’ ‘street checks,’ or their insistence on ‘de-escalating community members’ (with the obvious effect of doing the opposite), the common response is: “there is no alternative.” That’s simply not true – there are alternatives; there are interventions that don’t involve lethal force; there are systems of care that don’t rely on carceral logic. The problem is that these alternatives don’t get hundreds of millions dollars annually. In 2021, organizers from across so-called Canada came together to issue a statement entitled Choosing Real Safety: A Historic Declaration To Divest From Policing And Prisons And Build Safer Communities For All. This statement highlights the way cruelty–rather than real solutions–is funded:

Our public funding of policing, jails, prisons and immigration detention vastly exceeds the funds allocated to public housing, income assistance, childcare and mental health support. We can choose differently.

–Choosing Real Safety Declaration, 2021

Ending police violence means removing police as first responders; it means investing in preventative systems of care; it means decriminalizing survival activities. Ending police violence means ending our reliance on police and prison oversight, commissions and inquiries as the sole guideposts to building a better world. Every life taken while in police or prison custody represents a profound collective failure. We must understand how systems of criminalization encroach on people’s lives, and then justify who is worthy of life or death, care or cops.

Remembering Indigenous people killed by police & prisons in so-called British Columbia in the last 5 years:

- Dale Culver, a Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan man, died during an RCMP arrest in July 2017

- Lindsey Izony, a Tsek’ene woman, died in Prince George RCMP custody in July 2019

- Everett Patrick, a member of the Lake Babine Nation, died in Prince George RCMP custody in April 2020

- Mike Martin, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, died in BC Corrections (Surrey) custody in November 2020

- Douglas Cody Terrico, a prisoner at Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village died while in provincial custody in December 2020

- Julian Jones, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, died during an RCMP arrest in March 2021

- Yannick Lepage died in BC Corrections custody (Surrey) in July 2021

- Jared Lowndes, a Wet’suwet’en man, died during a Campbell River RCMP escalation in July 2021

- The unnamed and unknown, those whose names & lives have been stolen from us

Organized by #JusticeForJared, Honour their Names runs from March 15-19 at Gallery Gachet. Full event details are available on facebook. The show opens with a community feast and gathering on March 15, International Day Against Police Brutality. The show is free and open to the public from 12-6 PM daily.

Meenakshi Mannoe is the Criminalization & Policing Campaigner at Pivot Legal Society. She is also a member of the Defund 604 Network and Vancouver Prison Justice Day Committee, where she organizes alongside abolitionists collectively dreaming of a world without police and prisons.