Homelessness

A house fire on Pandora Street took three lives last Thursday. The event instigated the right-wing NPA to call for an inquiry. However, to...

Hi, what are you looking for?

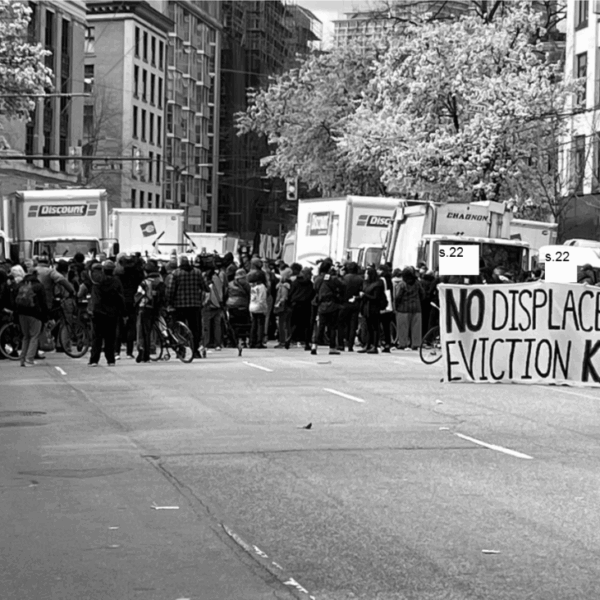

On the evening of April 5, 2023, as the first day of the Hastings decampment operation came to a close, Vancouver Mayor Ken...

A house fire on Pandora Street took three lives last Thursday. The event instigated the right-wing NPA to call for an inquiry. However, to...

Last month City Council adopted the Mount Pleasant Community Plan (MPCP). The MPCP, the culmination of three years of community feedback and consultations, is...

We previously reported that on Jan 20 2011, Vancouver City Council will consider a proposal to build seven condo towers in the Downtown Eastside,...

In addition to rent increases caused by the upscaling and renovation of dozens of low-income buildings around the city, Vancouver is losing affordable housing...

Vancouver City Council will hold a special meeting this Tuesday, Dec 12, to look over the proposed municipal budget. An administrative report distributed November...

Longtime Downtown Eastside advocate Jean Swanson has written a letter to City Council and City staff strongly urging them to "hold off on giving...